Having worked for a moulding operation that was acquired by a progression of different owners, with other companies also brought into the mix, Joe Bowes, managing director of Plastic Parts Direct, finally landed up at one in Banbury that grew during the ‘90s from nothing to 60 injection moulding machines in just 10 years, all based on the use of aluminium mould tools.

With that business sold and merged, Bowes and a partner set out to build their own business. The early 2000s were of course, just the time when China was ramping up in the mould tool and moulding area. The new company was caught by that and saw, for example, a third or more of business in giftware disappear, which prompted a move further into contract moulding. “However, we asked ourselves, ‘what is our safety net?’ Well, we didn’t have one, so we needed our own product,” the co-founder explains.

This saw the company go headlong into the glazing, or fenestration, industry, starting in 2006, producing items that are used by those making and installing double glazing frames. Today, that business accounts for 70% of the company’s £1.5m sales, backed by stock on the shelf and next-day delivery. Overall, the 14-employee company produces some 4 million mouldings/month, all in thermoplastics, with, again, 70% going to the glazing industry.

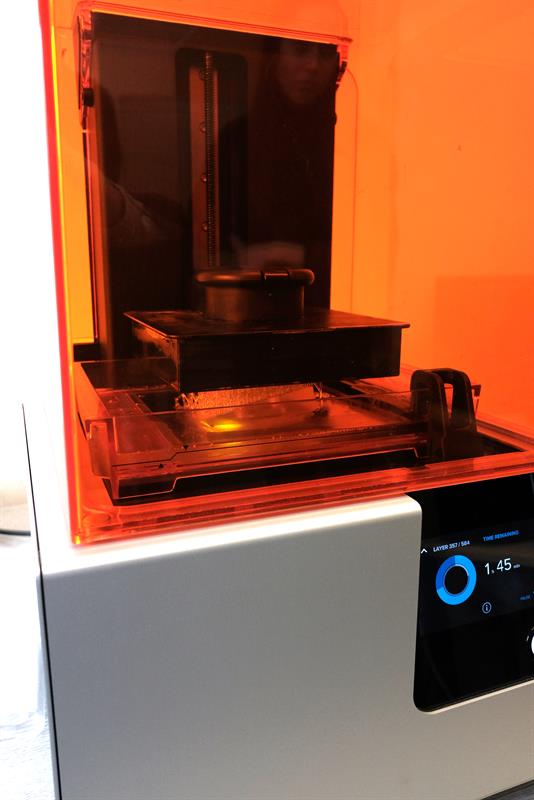

This traditional business has, however, been supported since around 2012 by 3D printing. Explains Bowes: “When 3D printing came along, we took a look at what that could offer. The general process for designing and making an injection moulding tool is that you get the part drawing and you get your 3D and you check it as best you can. You hope everyone's got their sums in order, make the tool, get it onto the moulding machine, sample it and then you find that it doesn't clip together, or something. So, the tool is taken off the machine, it is stripped down and modified. A long process. So, we put out a couple of trial parts to 3D printers, using the parts to check the design to see if it fits and works. Only when we know the design is correct do we make the tool. It’s saved us a fortune.” The initial experience was with Stratasys FDM (fused deposition modelling) machines and that is the technology employed today by Plastic Parts Direct, which now has three Stratasys machines for prototyping, although one is really a trial machine.

Continues Bowes: “That was the initial drive for us to go into 3D printing, for our own purposes, not for anybody else. But then our customers would say they had various parts that they wanted to print first and found that we had 3D printers. So, we printed parts for them and then we started making jigs and fixtures for them, too, in support of machining operations, for example. Simple operations like drilling, but the aluminium jigs that they were getting made were costing several hundreds of pounds. 3D printed versions were around £120. That would have been around 2014.”

Now, this 3D printing of sample parts for customers didn’t translate into follow-on mould tool and moulding business for Plastic Parts Direct. Much would go on to be made in China. But the company has built its mould tool and moulding business up another way, competing on cost and delivery for tools, and latterly as even that proved unable in some circumstances to provide a cost-effective solution has honed its 3D printing expertise to deliver a new service, injection moulded parts from 3D-printed tooling.

Explains Bowes, in the company’s build-up years, it was making one or two steel moulds a month, but over the past few years Plastic Parts Direct has increasingly promoted modular tooling (pre-made, standardised bolsters and pre-cut cavity blanks), mostly in aluminium backed by high speed machining of cavity details. That high speed machining has been delivered via a Hurco machining centre and a Nakanishi 50,000 rpm electric spindle attachment (TS Technology) that allows cutters down to 0.8 mm diameter to be employed. Zero-point workholding has also boosted productivity in the manufacture of modular tooling. Today, up to eight mould tools a month are now being made, with that increasing month on month, reports the managing director.

This increasing volume of modular tools over recent years has been driven by a growth in the number of jobs requiring shorter runs. Standardised modular tooling can be available in two weeks versus four to eight weeks, is less costly overall, with the further benefit of aluminium modular tooling being a £2,000 advantage over steel, important if only 1,000 parts are required. So, customers have moved to that lower cost solution. There have to be some concessions made on, say, sharp corners – that 0.8 mm cutter, so 0.4 mm radius, is as good as can be machined, otherwise its EDM, which is extra cost and time.

On production run length, Bowes cites an eight-year old eight-impression aluminium mould tool that is still making 240,000 units/month. This longevity issue is the one that customers require some convincing on, he says. Moving parts in aluminium mould tools will see them wear faster, he admits, while surface finish can be much better from steel moulds. However, since many of the parts moulded are not visible when in use, finish is incidental.

Over the past three or four years, new product projects have become a growing proportion of the enquiries being fielded today by the company, with as many as three-quarters looking for very short runs, many of them for product trial purposes. Small annual volumes of existing assembled products are also a driver, with companies looking to substitute more expensive part machining for moulding, again meaning low quantities. “So, they don’t need many parts, but they do need mouldings, not 3D-printed parts,” Bowes emphasises, adding that quantities in some cases can be just a few 10s of parts, maybe up to 500. Cost-effective as it may be, modular aluminium mould tooling, even at the base price of £3,000, is going to struggle to offer a competitive answer versus machining, so almost all enquiries of that nature died, he reports, adding: “There’s nothing to fill that gap between moulded parts and machined parts. But it occurred to us that we could 3D print the tooling; surely that’s got to work, we thought.”

3D printing a mould tool cavity

So started a journey of 12-18 months’ development work to establish the process to get to a point where results were good for a certain selection of parts. Says Bowes: “Not everything suits it. So, at present, and I mean at present because materials are changing every month, simple products without fine detail or moving parts in a soft to medium plastics are possible. But the cost is just a few hundred pounds for such tools.”

Obviously, because 3D-printed tools do not disperse heat, with cycle times three to four times longer than they would be in metal tools, consideration has to be given to, for example, material, ‘residence time’ in the barrel and the ability to remove the parts by hand. For quantities of 100, ejector pins are likely to be part of the tool. Steel sprue inserts are employed to prevent damage in the moulding machine.

The big challenge in being able to realise this is how to keep 3D-printed materials flat, and it is this nut that the company has cracked - the materials are available to anybody, with TPE or TPU typically found best. How the insert is then loaded to the tool is another part of Plastic Parts Direct’s magic. The tools are produced with 50-micron layers, or for a super-smooth mould cavity finish, 25 microns.

Importantly, if the company takes on a job on the basis of 3D-printing the mould tool and, for whatever reason, that doesn’t work, the customer is not left high and dry. “Part of the service, if we choose to send a customer down this road, is the reassurance that, should that not work, we produce an aluminium tool and the price to the customer is the same. We do not let the customer down,” Bowes assures.

The company is still at the beginning of its journey, hybrid tools having metal inserts are a possibility, while 3D printing material development is rapid. A larger 3D printing machine is on the buy list, which will boost the current 140 mm cube tool edge length capability (giving a 100 mm cube part envelope). The hit rate on winning low volume work has jumped to around 25% now, with the company having produced 20-30 tools at the time of Machinery’s visit over a period of about 18 months. The official launch of the service was last November, with the 3D-printed tooling now a part of the company’s advertised service.

3D-printed tooling with moulded parts