A £10 million automotive centre of excellence in Leamington, announced in February, is just the latest investment for steel conglomerate Liberty House Group (LHG) that, with other family businesses, has spent 50 times that much in the UK since 2015.

The 50,000 ft² centre opening next year, being built to “accelerate its automotive sector growth” is located alongside Liberty Vehicle Technologies, which, as its name suggests, manufactures brakes and automotive parts for relatively low-volume vehicle markets, including motorsport (NASCAR), London Taxis, US yellow school buses and the Warrior Land Rover. No doubt it will work closely with Daventry-based motorsport mechatronics firm Shiftec (www.shiftec.com), LHG’s newest acquisition, also announced in February.

But LHG’s automotive offerings aren’t all like this. Far higher part production volumes are produced nearby at the 33,000 m² plant of Liberty Pressing Solutions (formerly Covpress) in Coventry, officially inaugurated in late February. The 750-employee presswork firm makes body-in-white and trim components, and is a Tier 1 supplier to Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), Renault and GM.

Gupta speaks with Nick Hurd, Minister of State for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, at Liberty Pressing Solutions

Douglas Dawson, Liberty Engineering Group CEO,says the vehicle technologies businesses and car parts production businesses work together to mutual benefit; these kind of synergies are a LHG speciality. He told Machinery: “In particular, the vehicle technologies business is the ‘calling card’ for more mainstream automotive contracts. It shows the world that we’re serious; we’re not just a capacity-driven business,we’re innovative, there is more about us.”

The automotive centre of excellence marks a shift in strategy for the company, as it is LHG’s first development project uniting multiple businesses. According to Dawson, automotive contracts make up “quite a large part” of the activities of Liberty Engineering Group. It has seven divisions, each of which starts with the word ‘Liberty’: Vehicle Technologies and Pressing Solutions (both mentioned above); Vehicle Products; Tubular Solutions; Distribution; Performance Steels (a West Bromwich steel strip manufacturer); and Forging Europe of Poland.

Most of these businesses were inherited in 2015, through the acquisition of varied metalworking producer Caparo plc. In December 2015, referring to those operations, executive chairman of LHG Sanjeev Gupta said: “Despite current difficulties, advanced engineering can create enormous value for the UK economy, and I’m convinced that, based on the right business model, operations like these have strong growth potential in the UK and across various markets internationally where Liberty is present.”

Last month, the company also hosted the first meeting of the Lochaber Delivery Group, a public-private regional development panel supporting another much larger automotive-facing project: a £120 million initiative to build a new-build alloy wheel casting facility at the Fort William, Scotland, aluminium smelter that was bought by LHG last year. That facility, Britain’s only operational aluminium plant, has a production capacity of nearly 50,000 tonnes/year, and LHG plans to at least double that through a factory optimisation programme.

MOLTEN SUPPLY ON TAP

The planned factory, Britain’s first alloy wheel casting plant, would receive molten aluminium from the smelter and pour it directly into casting pots, saving the energy that would be required to re-melt alloy needed to start wheel casting elsewhere. Factory capacity is envisaged as reaching up to two million units per year, consuming 20,000 tonnes of aluminium, Dawson says.

This project is a microcosm of LHG’s vision of uniting metalmaking and metalworking in an integrated package, each aspect benefiting from the other: the smelter gets a ready customer; the wheel plant, a molten material supplier. And the supply chain may grow even tighter than that;

a portion of future aluminium might be processed into sheet for lightweight automotive body parts at its Coventry pressing business, perhaps increasing the amount of aluminium processed there, currently 5,000 tonnes, to parity with steel production at 65,000 tonnes per year, further driving the smelting operation.

The smelter also came with most of the electricity to operate it, in the form of the Fort William and Kinlochleven hydro power plants (85 MW capacity). These operations provide low-cost electricity that is essential to the process and to the smelting unit’s economic competitiveness. In addition, last month the site inaugurated a new £10 million biodiesel power plant, 20 MW capacity, enabling the plant to operate at full capacity even when dam waters run low.

Gupta’s vision, dubbed ‘Greenmetal’ or ‘Greensteel’,goes beyond the automotive supply chain, beyond engineering companies and beyond steel. It aims to do no less than rebuild the UK’s metals industry, and not by buying and refiring blast furnaces such as at SSI’s Teeside Steelworks in Redcar, shut in 2015. Says Dawson: “We don’t have any iron ore or coking coal in this country. So our steelmaking ambitions are almost flawed before they start, because the raw materials are imported and subject to global capacity demand and global currency fluctuations.”

Instead, LHG’s steelmaking vision is based on a process that is new to the UK: melting recycled scrap steel in electric-arc furnaces. LHG quotes an (unnamed) Cambridge University report that found that 70% of UK scrap is exported, and that the amount of scrap produced will rise from 10 to 20 million tonnes a year during the next decade. This scrap becomes the raw material feeding this new type of UK steelmaking business, following the successful model used by US steelmakers Nucor and Steel Dynamics, for example.

Last summer, during the run-up to a bid to acquire all of the shares of Tata Steel (the effort fell through in July), Gupta recorded a speech in a to-camera video. He said: “Steel is right at the heart of the manufacturing ecosystem, so if we can’t make steel competitively here, then we’re far less likely to hold onto industries that make products from this iconic material. But the reverse is also true. If we can find a way to make steel profitably in the UK, we can not only preserve and increase the number of jobs in the steel industry itself, but we can develop a whole host of high value sectors that feed off this most versatile of metals.”

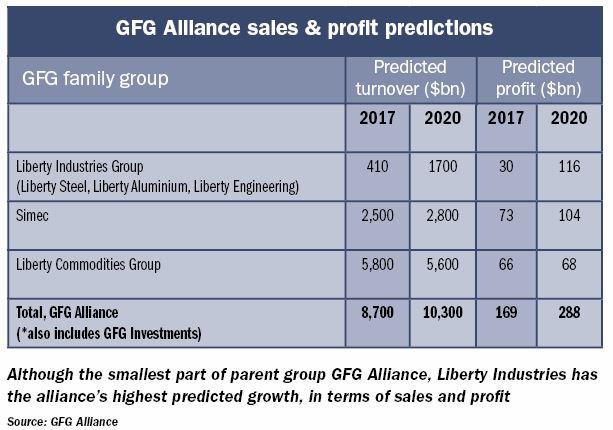

And what LHG and parent company GFG (Gupta Family Group) Alliance has been doing is buying up all of the steel businesses going: as metals producers and steel mills have shut, gone into administration or in some other way proven an attractive target, they have been snapped up. Major purchases include, in 2013, MIR Steel Newport;in 2015, Caparo plc operations; in 2016, disused Thamesteel Sheerness Docks site, Tata Steel’s Dalzell and Clydebridge steel mills, Rio Tinto’s Fort William, Scotland aluminium smelter; and in 2017, CovPress and Tata Speciality Steels.

INTEGRATED STEELMAKING?

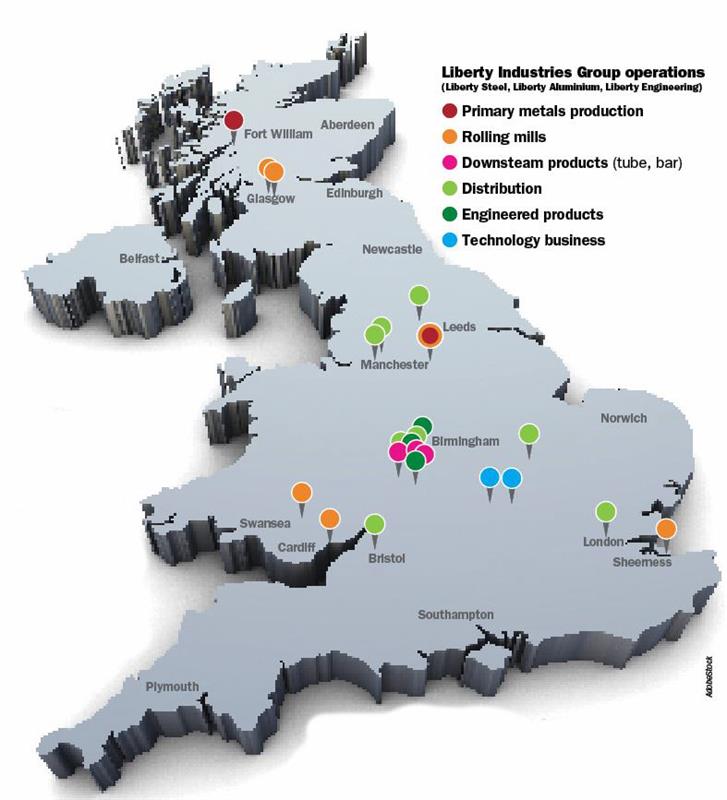

Now, one part or another of the GFG Alliance owns elements of every part of the steel and aluminium-making process. These include a scrap collection business(aiming to ramp up to capacity of 5 m tonnes/year) and melt shops in Sheerness, Stocksbridge and Rotherham(the latter offering annual liquid steel capacity of 1.1 million tonnes) plus the aluminium smelting operation in Scotland. Then there are the steel mills making upstream products in Scotland, the Midlands and Wales (Newport alone has a rolling mill capacity of 1 million tonnes/year) and other producers making downstream products such as tube, strip, hollow sections and wire steel mills. Metals’ distributors in the north, midlands and south transport these products to customers, including LHG’s own value-add components and design engineering firms in the midlands.

Providing the electricity for the meltshops are intended to be electricity plants powered by renewable energy,just like in the Highlands. LHG’s sister group in the GFG Alliance, Simec, runs power plants in Scotland and Newport (Uskmouth, 393 MW capacity, biomass/coal cogeneration plant). Also, Simec has announced plans to build a total of 14 mini-power plants to generate a total of 200 MW from biofuel sources during peak times. The company is lobbying government to remove the carbon tax on power plants supplying steel mills; it has become a significant supporter of Tidal Lagoon Power, a Swansea tidal power plant (https://is.gd/uyelip).

Internal business from other subsidiary companies, either upstream or downstream, is a big part of company activity in total. For example, Liberty’s Tredegar (Wales) steel pipe and tube factory, reopened in May 2016, is to be fed hot-rolled coil from Newport. At that time, Gupta said: “The global oversupply of steel increases the need for the UK to focus our industrial strategy around both reducing costs and adding value to steel...Our plan is to restructure the sector around production efficiency, engineering integration and innovation”.

However, LHG’s businesses are not obligated to supply each other, nor are they incentivised financially to do so. Says Dawson: “We don’t have an exact policy of ‘you must buy from your sister company’, but it is our preference. The preference lies in that, in good times, where there is lots of margin available … there’s lots of room for that make-or-buy conversation, whether it’s between sister companies or whether it’s a company deciding to outsource or not. But we live in a cyclical industry, a cyclical world, and in bad times it’s always far better to be fully integrated.”

He says that this approach is also one currently favoured by the group’s big carmaking customers. He gives an example of the BMW Mini anti-roll bar production. This starts from hot-rolled coil, is made into tube in another LHG operation, then passed to the components business that manipulates it and finishes it. Dawson says that BMW favours this kind of integration because one supplier can exert absolute control over quality of multiple stages of production, and just-in-time delivery. Other benefits of integration include the ability to offer increased customer service, such as downstream processing in the form of laser cutting or profiling – and greater control of costs.

As integration offers greater security of supply, it is even providing post-Brexit comfort to large carmakers. The term ‘supply chain securitisation’ has been coined to refer to supply lines protected from the risk of future tariffs or other Brexit uncertainties. In addition, automotive primes are looking for larger suppliers to consolidate the supply chain, and for key suppliers to become more relevant – which means offering them a greater variety of products.

Concludes Dawson: “It’s an old saying, talking about a one stop shop, but it works.”

* Douglas Dawson will be speaking at the Manufacturing & Engineering North East conference and exhibition, Newcastle,

5-6 July 2017.

First published in Machinery, April 2017