The UK-wide apprenticeship levy comes into being next year, on 6 April. Just last month, the government unveiled proposed funding ceilings that the various apprentice frameworks and apprentice standards will attract (see box at end ‘Training expenditure ceilings’). Comment on these were invited by 5 September.

Firms of a certain size will pay a levy (tax) that they then get back in the form of digital funds (see later) to pay for apprenticeship training. But levy-supported training funds will not just underpin the training of apprentices in levy-paying companies. According to EEF’s Tim Thomas, director of employment and skills policy, the cash will be “the only source of apprentice funding in England”. And the pot is split a number of ways, supporting: levy-paying companies; non-levy-paying companies (through training top-ups); home nations’ training efforts (see later); additional funding for 16–18-year-olds, the EEF “hopes”; plus additional funding to boost English and maths education. So this clearly implies that the government expects some companies not to take up all their vouchers and for some not to take up any, if the well is not to run dry or, worse, be oversubscribed.

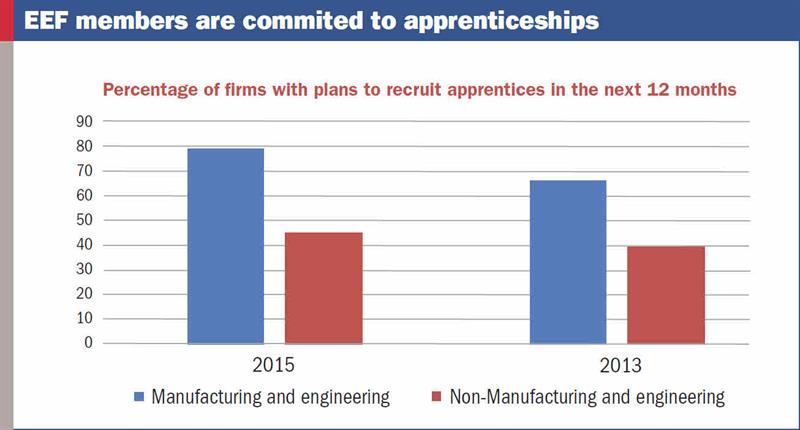

Through the levy, the government aims to achieve an additional three million apprenticeship starts in England in the five years to 2020 and offset falling employer investment in training, although that is something the EEF contests for its sector (see diagram, below). The move to a levy will also return significant savings to the UK Exchequer – more than £3 billion in 2020/21 (http://bit.ly/1TsdLES). But while this is an English target – because training is devolved to home nations – all companies in the UK will fall within the levy collecting system. The devolved training bodies will get a slice of the levy-derived funds, but it is up to them what they do with it.

EEF does not agree there is a drop in employer apprentice training (source: EEF)

Tackling non-levy payers first, according to the details released last month, non-levy-paying firms (around 98% of all employers in England) will have 90% of apprentice training costs funded, with the company ‘co-investing’ to get to the 100% figure. But that 90% proportion is limited to the appropriate funding ceiling, so a company might have to pay more than 10%, in fact.

Employers with fewer than 50 employees will have 100% of training costs paid for by government, if they take on apprentices in the 16–18-year-old group or young care leavers.Same principle again for that 100% as for the 90% contribution, however.

LEVY-PAYING COMPANIES

Turning to levy payers, these are those employers having a wage bill of over £3 million; they will pay a 0.5% levy on that figure, but will get a £15,000 rebate. So a company with a wage bill of £10 million will pay £50,000, less £15,000, so £35,000. An employer, by the way, is anybody that pays secondary NICs – although EEF reminds companies that apprentices under 25 are not subject to such NICs.

Digital funds in excess of the funding band ceilings cannot be spent on an apprenticeship; the company must make up the difference. But it could spend less and benefit from retained funds that it could, in theory, spend on more apprentices.

For levy payers that spend all their training vouchers but who want to employ more apprentices, the government is proposing that 90% of the additional costs will be supported (same rules for the 90% as stated before).

Levy payers, non-levy payers and training providers get an extra £2,000 per trainee when taking on 16–18-year-old apprentices or young care leavers.

It is expected, the EEF says, that the levy will be collected monthly, along with PAYE and NI, and that funds supporting apprentice training will similarly be released monthly but with 20% withheld till apprenticeship completion. And those funds for 2017/18 will be topped up by 10%, so as to make sure employers get out more than they put in, the organisation adds.

Now, as with all things, this rather straightforward explanation has some wrinkles. For example, what happens if your wage bill either rises above or falls below the £3 million? Such details are still being worked out, EEF’s Thomas offers.

The EEF has its own training centre, located in Birmingham, where it undertakes apprentice training. The centre is currently undergoing expansion

But how might companies react to this new system? According to the EEF, a majority of levy payers are not confident that they could spend all their levy funds on apprenticeships. The organisation is undertaking further work with its members, with a requested expansion of the activities that levy funds can be spent on likely to be the outcome. Extending it to cover the costs of employing apprentices or in support of traineeships (see Machinery, August 2016, p14) are likely suggestions.

But with the majority of employees in companies not paying the levy, it will be the actions of the smaller companies that will be key in boosting numbers to reach the government’s three million target figure.

And helping smaller companies take steps to employ apprentices is part of the government’s vision, as set out in ‘English Apprenticeships: Our 2020 Vision’ (https://is.gd/sT3vkJ). In brief, relevant efforts here take in removing barriers that prevent companies from acting on their initial wish to employ apprentices, and also in modernising apprenticeships to make them more appropriate.

The latter is being achieved via the so-called Trailblazer apprenticeships across a range of sectors to develop new apprenticeship standards. There are defined core principles of quality for an apprenticeship that must be adhered to (see box at end – ‘Training expenditure ceilings'). The former barrier is being supported by the creation of the Digital Apprenticeship Service (DAS) and associated services. DAS will go live from 2017, but will be tested this year. Through this platform, digital funds will be paid in for employers to draw down to spend on apprenticeship training; they can also advertise apprenticeship vacancies on DAS. Important to note is that funds will expire 18 months after they enter a digital account, unless they are spent on apprenticeship training.

FURTHER SUPPORT FOR SMALL FIRMS

Alongside DAS, and in particular aimed at small companies, the ‘English Apprenticeships: Our 2020 Vision’ publication says: “Integrated with the Digital Apprenticeship Service that we are putting in place, we will continue to offer an online and telephone helpline to support smaller businesses with choosing the right apprenticeship frameworks or standards, the best training providers and advertising for an apprentice.

“We will also work with local partners across the country, including local authorities, Chambers of Commerce and training providers, who provide front-line support to employers as they prepare for and hire their first apprentices.”

And DAS will also support smaller companies by allowing for the diversion of funds from larger companies to smaller supply chain firms, with 10% of funds in one company’s account being transferrable to another employer’s digital account from 2018 (in fact, this transfer capability is available to all firms). By 2020, all employers will be able to use DAS to pay for training and assessment for apprenticeships.

So, the new training system and infrastructure is taking on more understandable form and Semta, for one, is fully on board. Says Ann Watson, CEO of the not-for-profit employer-led organisation charged with skilling engineering and advanced manufacturing: “There is much to be welcomed by our sector. The successful introduction of the apprenticeship levy is now absolutely vital to the future of our sector and our nation – Semta is totally committed to help make this happen.

“The transferability of levy funds to other employers and the full funding by government of younger apprentices taken on by small employers are particularly pleasing.

“Over £350 million a year is spent on apprenticeships in our sector, 25% of the total. It’s crucial that employers are able to maintain this level of investment in their skills, so we welcome the generous 90% co-investment proposed by the government and the uplift for STEM apprenticeships.”

❏ For more detail, visit ‘Apprenticeship levy: how it will work’ at http://bit.ly/1SYtZ88

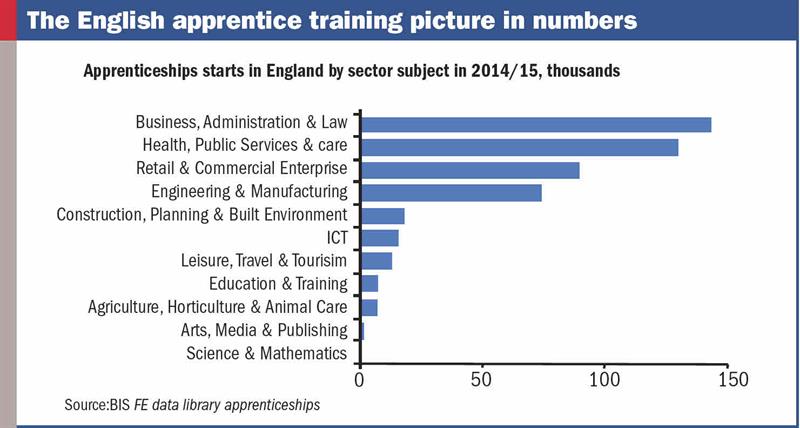

Engineering and manufacturing is the fourth largest trainer of apprentices in England

TEXT BOX

Training expenditure ceilings; apprenticeship frameworks and standards

Published last month are the current proposed apprenticeship framework and apprenticeship standard investment ceiling limits (complete listings available at https://is.gd/qk1rnS). These give the maxumum figures that government will contribute. There are 15 funding bands, with engineering and manufacturing standards/frameworks having been allocated across all 15 of them, says EEF, although core engineering manufacturing activities tend to fall between 9 and 15. Interestingly for manufacturers, EEF says that government has recognised that current funding for STEM apprenticeships is below the real cost of training and these have been increased in the funding bands, with a 40% uplift for Level 2 (GCSE) STEM apprenticeships and an 80% boost for Level 3 (A-level) STEM apprenticeships.

As an example of the proposed funding levels, the ‘Aerospace Engineer’ apprenticeship standard, a Level 6 (Bachelor’s degree) undertaking, draws a limit of £27,000 funding, being placed in the top band (15); a Level 3 ‘Aerospace Manufacturing Electrical, Mechanical and Systems Fitter’ apprenticeship standard draws £24,000, placing it in band 14, while ‘Machinist (Advanced Manufacturing Engineering)’, another Level 3 route, is supported to the tune of £21,000 (band 13). By way of contrast, an ‘Engineering Manufacture, Aerospace’ apprenticeship framework draws £9,000 for this Level 3 undertaking, with the Level 4 (Higher National Certificate) ‘Manufacturing Engineering, Aerospace’ pathway also drawing £9,000.

Apprenticeship standards are taking over from apprenticeship frameworks. Their development is led via ‘Trailblazers’, which are employer-led groups made up of companies in a particular sector that have come together to, essentially, redesign the old frameworks.

These new standards cover a job in a skilled occupation that is defined by these criteria:

- Requires substantial and sustained training, lasting a minimum of 12 months and involving at least 20% off-the-job training

- Develops transferable skills, and English and Maths, to progress careers

- Leads to full competency and capability in an occupation, demonstrated by achievement of an apprenticeship standard

- Trains the apprentice to the level required to apply for professional recognition, where this exists.

And fundamentally, apprenticeship standards must be more than just training for a single job or employer; they must ensure that apprentices can adapt to a variety of roles with different employers, and develop the ability to progress their careers.

These new standards see the frameworks significantly cut down (in terms of length), with some standards having the key information on two sides of A4 paper. As the government pointed out in its December 2015 document ‘English Apprenticeships: Our 2020 Vision’ (https://is.gd/sT3vkJ), there are currently around 230 apprenticeship frameworks and over 700 pathways within them. “Some are overly prescriptive, complex and long, others lack the necessary detail, and employers have criticised them for failing to equip young people to do the job. Under our reforms, employer-designed standards will replace frameworks, and will be clear and concise,” the document says.

At the time of the publication, it was stated: “To date more than 1,300 employers have been directly engaged in designing over 190 new apprenticeship standards, with over 160 more in development.”

In some instances, new standards do not include any qualifications; there is no requirement for qualifications to be included, in fact. However, in many of the engineering standards, employers have made the decision to include one or professional registration, so the learner has a transferable qualification.

This article was published in the September 2016 issue of Machinery magazine.