There is widespread misunderstanding about the status of trichloroethylene and its continued application as a degreasing agent. Some people believe it to be banned already, while others believe that a ban is imminent and certain, due to unclear information circulated by some regarding its proposed inclusion in Annex XIV of REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of Chemicals).

It is not banned and it is not certain that it will be, even though it is true that ECHA (the European CHemicals Agency) has recommended trichloroethylene's addition to REACH's Annex XIV.

An event was staged at degreasing specialist Kumi Solutions (024 7635 0360) during March to cast light on this much misunderstood area, with the degreasing equipment supplier supported by technical partner Safechem Europe (07976 531695).

SET UP FOR SAFETY

Safechem Europe, headquartered in Dusseldorf, is a subsidiary of The Dow Chemical Company, a manufacturer of trichloroethylene under the trade name Neu-Tri E, as well as other chemicals. Safechem Europe was formed some 20 years ago, explains Richard Starkey, UK regional sales manager, to promote and maintain the safe continued use of The Dow Chemical Company's chemicals, including trichloroethylene, as a response to legislation in various parts of Europe. In the UK, Safechem Europe does not simply supply chemicals, but is a technical division responsible for providing consultancy and supplying solutions to metal degreasing applications.

At the same time, Safechem Europe designed its Safe-Tainer system to support the safe transport of trichloroethylene (see box item) by distributers – there are some 22,000 Safe-Tainer systems in use throughout Europe. Trichloroethylene has continued to be slammed on both environmental and health grounds over that time, however.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer's (IARC) pivotal 1995 report (http://bit.ly/HhzdGf) helped provide evidence to back the reclassification of trichloroethylene as Risk Phrase 45, meaning the substance "may cause cancer", with the European Commission voting on 25 January, 2001 to reclassify it from R40 to R45, a category 2 carcinogen. A point to note is that the European Chlorinated Solvent Association "continues to believe that science does not justify this labelling change" (http://bit.ly/HdXKtr). And in the US, trichloroethylene is stated as "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen" since the 9th Report on Carcinogens (2000), with a move in the 10th report on Carcinogens to get it changed to "known to be human carcinogen" failing. The HSE website points up a new report looking at trichloroethylene data since the 1995 report (http://bit.ly/Hf90Lq) and a line from this states: "Overall, the picture [for trichloroethylene] has hardly changed since the evaluation by IARC, when it is considered that some of the negative studies cannot be considered as very informative."

However, for the UK, this reclassification meant that COSSH regulations applied to the chemical's use, which asked for "substitution, using an alternative solvent or cleaning process, or, if this is not reasonably practicable, enclosing the degreasing process, as far as is reasonably practicable". Alongside that, the HSE recommended maximum exposure limits of 100 ppm (8 hour exposure, TWA) and 150 ppm for short-term exposure (15 mins, TWA) for trichloroethylene – there is no Europe-wide agreed OEL.

SOLVENT EMISSIONS DIRECTIVE

The Solvent Emissions Directive (SED) 1999/13/EC, which came into force in England and Wales in March 2002 (Scotland, January 2004; Northern Ireland, February 2004) set out to limit the use of environmentally damaging organic solvents. For trichloroethylene users consuming more than 1 tonne, there were requirements laid down on reducing fugitive emissions, while substitution was also suggested as a way forward. And from October 2007, for all installations (existing and new), companies covered by the SED should have decided on the route of compliance they wish to take and submitted a Solvent Management Plan for review by the appropriate regulator.

To close the loop-hole for those companies using less than 1 tonne/year, suppliers of trichloroethylene voluntarily agreed not to supply to companies that were still using open-top tanks, with this coming in to force on 1 January 2011. This even though COSSH had already asked, where no substitution occurred, for "enclosing the degreasing process, as far as is reasonably practicable". (The voluntary agreement was also key in another move, see later.)

Now, while both the SED and COSSH call for substitution of trichloroethylene where possible, it is not mandatory. If an alternative cannot be found on grounds either of performance or cost, users can continue with its use, abiding by other elements of COSSH and SED.

Moving to REACH, inclusion on the Candidate List - currently numbering 73 items - means that suppliers of such substances "in a concentration above 0.1% have to provide sufficient information to allow safe use of the article to their customers within 45 days after receiving the request". Trichloroethylene was put on the list in 2010.

And being on the Candidate List means that these substances will progress through to the next stage, Authorisation, which means that authorisation must be sought for continued use in an application. If no authorisation is given, then the chemical cannot be used for that process after what is called the 'sunset date'.

The REACH process explained

The European CHemicals Agency (ECHA) proposed to the European Commission at the end of last year that the Commision should prioritise trichloroethylene for inclusion in REACH Annex XIV. This is the latest move and has prompted fears of an imminent ban; hence the Kumi Solutions event.

Now, over the past 20 years, as the waves of legislation have arrived, so The Dow Chemical Company and Safechem Europe have worked with degreasing equipment manufacturers such as Pero (Kumi Solutions) to develop machine and chemical technology, says Mr Starkey. "For example, service considerations. How can we extend the life of the solvents; how do they behave in enclosed degreasing systems. From that have come such things as the Maxicheck test kits and Maxistab stabilisers, plus the ability to deal with modern, high technology additives – oil isn't just oil anymore."

Safechem Europe also offers a process leasing program – Complease - that enables users to lease the entire cleaning process, including closed cleaning equipment, Dow solvents, the Safe-tainer system and Safechem Europe's package of supporting services and technical expertise.

More recently, Safechem Europe has also put together training material to support the safe use of equipment and trichloroethylene by operatives, via its Chemaware programme.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

But what next? Mr Starkey is cautious about providing hard and fast dates, but has this to say: "As far we know at the moment, the earliest that trichloroethylene will find itself listed in REACH Annex XIV is February of next year. And that listing will mean that, unless there is authorisation sought and then given for an application for the use of trichloroethylene, it will not be available at a future date for that application."

However, he adds that, according to ECHA, the work involved will mean that an application for authorisation is likely to take 18 months, which means that the anticipated date for an application is August 2014 (18 months after February 2013). "Following that, the time to undertake the authorisation process is reckoned to take a further 18 months, so, failing any authorisation for a given process, banning will apply from February 2016 at the earliest," the Safechem expert explains. This February 2016 date is officially termed a 'sunset date'.

But he says: "The Dow Chemical Company and Safechem Europe have made a request for exemption from authorisation for metal degreasing in closed systems for trichloroethylene. Part of the strength of this is that when Dow registered trichloroethylene (Neu-Tri) with REACH, it was never registered for use in open-top degreasers, only for use in sealed equipment and where the use is adequately controlled. (This specific use being part of the Voluntary Industry Agreement (VIC) referred to earlier, so the VIC was an essential part of the exemption request.)

"In addition, part of the request is for a new Europe-wide Occupational Exposure Limit. And we have taken the limits as recommended by Europe's Scientific Committee for Occupational Exposure Limits - 10 ppm (8 hour, TWA) and 30 ppm as a short-term exposure limit (15 min, TWA). As it happens, we have 20 years' experience with sealed technology and we know that we can achieve that. We also have installations where OELs are measured, so we can demonstrate it to be true."

This will require a legally binding OEL to be agreed and legislation enacted/amended, in the form of a directive – "And that could take anywhere from two to five years," Mr Starkey suggests, taking the latter figure from the UK's HSE. Because of that time frame, Dow and Safechem Europe have also requested that the February 2016 sunset date be moved back. Being listed on Annex XIV will be no barrier to exemption being granted, it is stressed, and ECHA have officially acknowledged Dow and Safechem's exemption request.

"We are currently focusing on gaining an exemption from authorisation for surface cleaning in closed systems, whereby a binding OEL of 10 ppm is in place. This is in addition to the safe supply and take back in the Safe-tainer system and training being supplied via Chemaware solvent training. If, however, exemption isn't granted, then we are already working on what options there are for authorisation," highlights Mr Starkey.

So, exemption will mean no requirement for authorisation, but authorisation would be the next step, were that to fail. Mr Starkey says: "When REACH was first conceived, it was anticipated that applications for continued use would be made by the downstream user – that is, the company that is actually undertaking, in this case, degreasing, with that requiring every degreaser to submit an authorisation dossier. It is now accepted, however, that a third party, a supplier, could undertake the authorisation process for an application. So, failing exemption, Dow and Safechem will tread that path."

However, authorisation isn't the end of it for any substance, as there are review dates following authorisation, and the review period "could be three years or could be five; we don't know", Mr Starkey offers, adding: "Nothing has yet gone through the authorisation process. This is all unknown territory for us, ECHA and the REACH committee."

ADVICE FOR CUSTOMERS

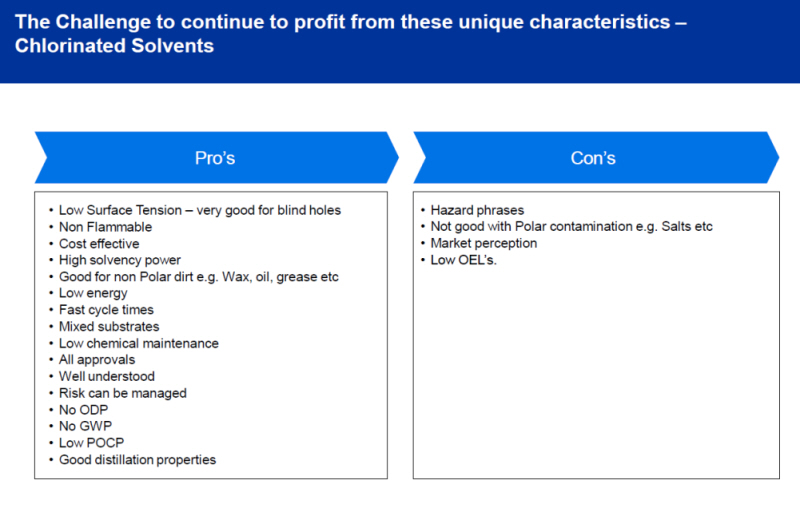

So, what should customers do that require the strengths of solvents, as opposed to aqueous, systems? Well, change to an alternative, following trials, such as Dowper MC, a perchloroethylene solvent and R40 classified, or Dowclene 1601, a non-chlorinated solvent, based on modified alcohols (hydrocarbon alternative) and R20 classified. Rolls-Royce has, incidentally, approved Dowclene 1601 as an alternative to trichloroethylene for vapour degreasing only, but has also stated it will stick with trichloroethylene until it is banned, Mr Starkey highlighted.

Kumi Solutions' managing director Simon Graham suggests that, for users of trichloroethylene that cannot change, and for those companies switching back to the solvent following a failed dalliance with aqueous, the sensible choice is a universal system that can, at a future date, be easily switched, on site, to a legal solvent alternative, if trichloroethylene were to be banned. Such a system has a premium of just €3,500.

And of the 65% of Pero's 125-150 machines/annum that are supplied for use with solvent, historically 80% are universals, with 20% supplied for use with hydrocarbons. That said, fully half of the machines on its shopfloor now are Dowclene 1601 – "A year ago that would have been a 20% mix of Dowclene 1601 and straight hydrocarbons, and clearly demonstrates a shift in Europe away from chlorinated solvents and mitigation of risk, with regard to REACH," says Mr Graham. In the UK, 65% of installed machines are universal, with 15% running hydrocarbons (Dowclene 1601), although the current order book claims 40% hydrocarbon units.

The UK, offers Safechem Europe, is the leading user of trichloroethylene in Europe for degreasing, so its and Kumi's advice and knowledge will be much sought after, it can be assumed, as the trichloroethylene story continues to unfold.

Additional information

[]

Safety in supply and collection

[]

Chemical properties and advantages

[]

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

[]

BAE Systems' votes for trichloroethylene

Safety in supply and collection

The Safe-Tainer system is a closed-loop state-of-the-art delivery system for handling chlorinated solvents. In combination with closed degreasing equipment or similar, it is said to represent "the best available technology" for the use of these products.

The Safe-Tainer system includes two different, specially designed double-walled containers. One is exclusively designated for the supply of fresh solvent and the other for the collection of used solvent. Both containers are delivered with a 216.5 litre drum inside. The outer steel box protects the drum, preventing damage or spills. The Safe-Tainer container is lockable and, as a result of its special base construction, it is easy to transport with a forklift truck or pallet lifter.

The Safe-Tainer container for fresh solvent is connected to the cleaning equipment in one single step. The motor is placed on the drive spigot of the pump unit and the solvent is quickly transferred to the machine. The expelled vapours can be returned to the container through an additional connection. A variety of accessories allow you to connect the Safe-Tainer system to all types of machines. Discharge of used solvent is similarly safe.

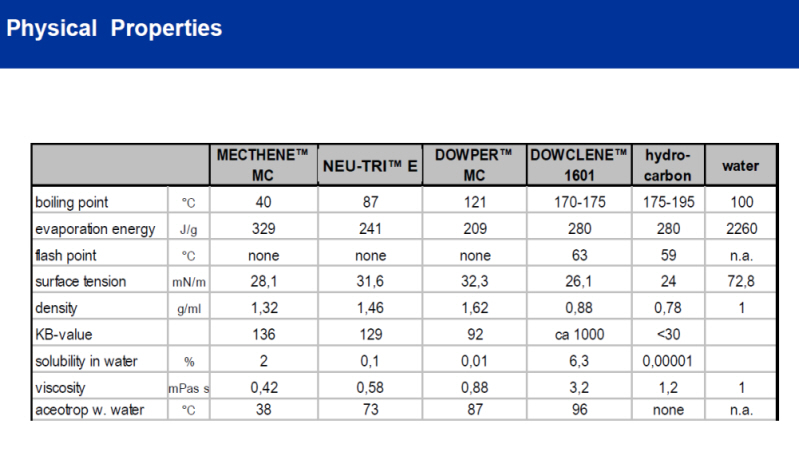

Chemical properties and advantages

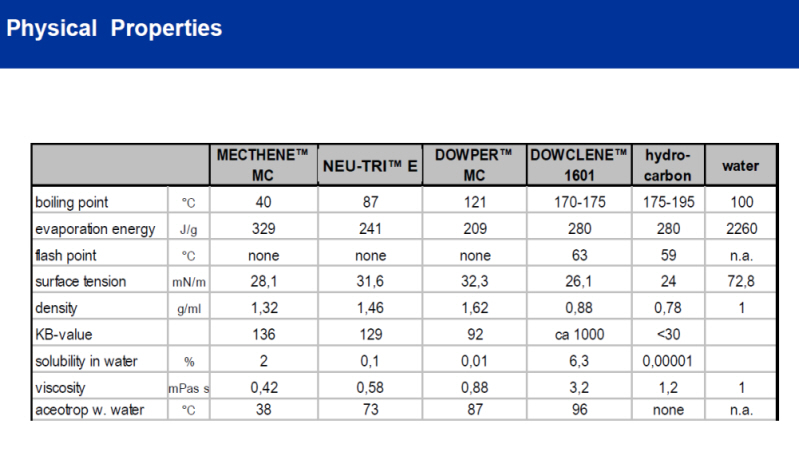

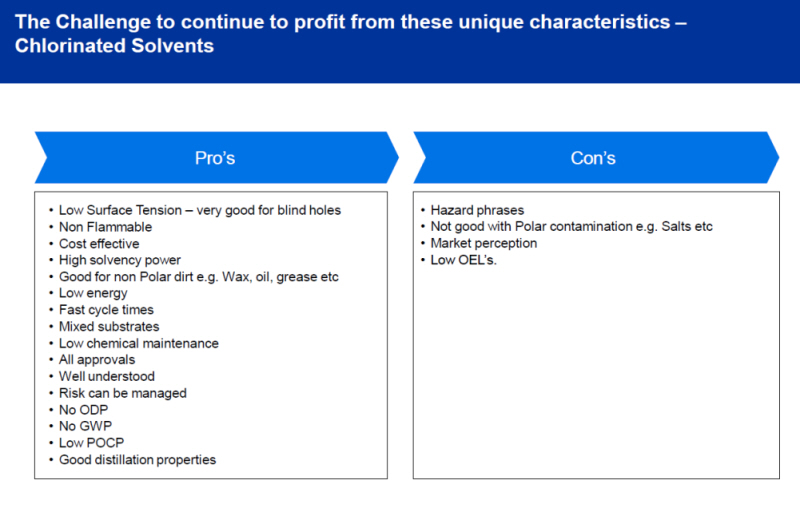

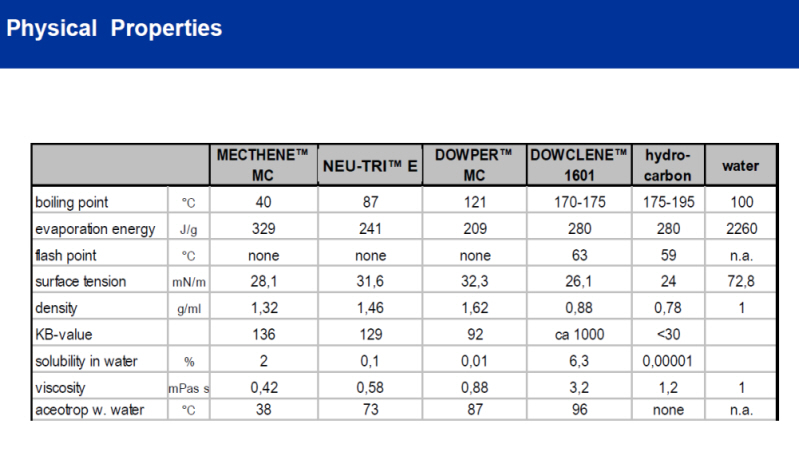

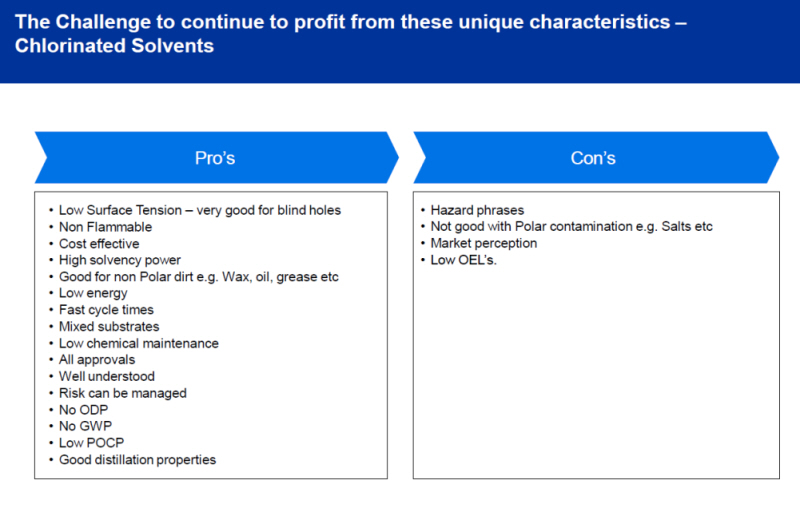

With a lower surface tension than water, chlorinated solvents, such as trichloroethylene, are very good at getting into difficult-to-reach places. The solvency power (KB) for oils is also high. Explains Mr Starkey: "There are a lot of positives for trichloroethylene, but we often spend our time defending it against negative comments, often emanating from companies offering alternatives.

"Degreasing with chlorinated solvents is well understood. The first trike degreaser out of ICI was in the 1920s – there's nothing we don't know about trike. All of the toxicity data is there and has been for years."

Indeed, he says an aerospace company put it like this: "for complex parts, it is much better to deal with a known risk than risk the unknown."

Trichloroethylene properties and advantages

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

A life cycle assessment (LCA) comparing the cleaning of metallic parts reveals that trichloroethylene used with modern technology has a lower overall environmental impact than aqueous cleaning. This was the overall conclusion of a 1997 study (Screening LCA of metalware cleaning processes) published by Ecobilan SA, a Paris-based specialist in conducting LCAs, and it is still considered to be the leading study on this matter.

An Ecobilan team collected environmental data from engineering companies in four countries between 1994 and 1996. Data on trichloroethylene production was provided from the ecoprofiles completed by member companies of the European Chlorinated Solvent Association (ECSA).

The study found that the main disadvantage of aqueous cleaning is water pollution, even when the user applied highly efficient physico-chemical with biological treatment of the aqueous cleaning residues. Depending on the site evaluated, eutrophication was found to be 200 to 2,000 times higher than with solvent cleaning.

With solvents, it was found that air acidification was higher due to emissions during cleaning. However, where equipment was fitted with an activated carbon recovery unit (ACRU) or has some form of enclosure air acidification was significantly less than aqueous cleaning with a drying stage.

Metal degreasing specialists from the Centre Technique des Industries Mécaniques (CETIM), an independent French technical organisation specialising in the mechanical industries critically reviewed the LCA. The CETIM review confirmed solvent cleaning as the right technique to be used when metallic parts needed to be dry for subsequent processing.

BAE Systems' votes for trichloroethylene

Cleaning in the aerospace industry is still often solvent-based, trichloroethylene, and it can prove a tough act to follow, as BAE Systems, Samlesbury had found. In order to improve quality, sustainability, and safety of the cleaning process, the company looked for an alternative cleaning agent. Over a period of four years, the company investigated pretty well all options, including water-based cleaning agents and other solvents such as hydrocarbons and n-Propyl Bromide (nPB), but none could match up to Neu-Tri E trichloroethylene offered by Safechem Europe, says the solvent supplier.

Only Neu-Tri E was capable of reliably removing all the contaminations that occur through the use of up to 16 different oils and greases during the manufacturing process, and this resulted in an approval for NEU-TRI E trichloroethylene by BAE Systems and massive reduction in solvent consumption.

The chlorinated solvent is used in a new, closed cleaning facility which operates under vacuum. It is designed to clean 12 aluminium sheets of 2,000 by 2,600 mm or a mass of 700 kg in one cycle. With this capacity, the new degreaser is the largest machine of its kind in Europe, and, potentially, the world.

The cleaning process is carried out fully automatically and includes high pressure spray washing, vapour degreasing, and vacuum drying. At the end of the 30 to 40 minute cleaning cycle, the trichloroethylene is collected, distilled, condensed and absorbed into a carbon bed within the facility, so no solvent fumes occur when the door opens.

The chemical is supplied using Safechem's Safe-Tainer closed-loop transfer system, a state-of-the-art delivery and handling system for solvents that consists of two separate, specially designed containers, one for fresh and one for used solvent. Each container is delivered with a standard drum inside, with the steel container protecting the drum, preventing damage or spills. The containers are easy to handle and to store, and allow the safe management of chlorinated solvents on site.

During solvent transfer to the cleaning machine, a leak-free, dry-break coupling prevents spills and vapour emissions. When transferring used solvent from the cleaning machine to the Safe-Tainer container, a dry-break coupling adapter and a vapour return connection prevent emissions. This safeguards the operator and environment from potential contact with the solvent.

This, in combination with a new state-of-the-art degreaser, has seen the consumption of solvent dramatically reduced - 5 tons a year to less than half a ton, while the system meets all specifications of the Solvent Emissions Directive (SED).

Safechem also offers a simple and efficient solutions to monitor and maintain the quality of Neu-Tri E trichloroethylene. Due to the rising concentration of oils and greases and their decomposition products that are removed from the aluminium surfaces in the cleaning process, the chlorinated solvent slowly degrades. Safechem's Maxicheck test kit and business logbook allow operators to check the alkalinity level and the acid acceptance of the solvent regularly in an easy and quick manner and plot the results. If necessary, Maxistab stabiliser can be added to keep stabiliser concentration at the optimum level. This not only supports maximum cleaning quality, it also helps BAE Systems protect its cleaning facility against acidification and corrosion, and minimise solvent usage via an extended life-span.

First published in Machinery, May 2012

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

A life cycle assessment (LCA) comparing the cleaning of metallic parts reveals that trichloroethylene used with modern technology has a lower overall environmental impact than aqueous cleaning. This was the overall conclusion of a 1997 study (Screening LCA of metalware cleaning processes) published by Ecobilan SA, a Paris-based specialist in conducting LCAs, and it is still considered to be the leading study on this matter.

An Ecobilan team collected environmental data from engineering companies in four countries between 1994 and 1996. Data on trichloroethylene production was provided from the ecoprofiles completed by member companies of the European Chlorinated Solvent Association (ECSA).

The study found that the main disadvantage of aqueous cleaning is water pollution, even when the user applied highly efficient physico-chemical with biological treatment of the aqueous cleaning residues. Depending on the site evaluated, eutrophication was found to be 200 to 2,000 times higher than with solvent cleaning.

With solvents, it was found that air acidification was higher due to emissions during cleaning. However, where equipment was fitted with an activated carbon recovery unit (ACRU) or has some form of enclosure air acidification was significantly less than aqueous cleaning with a drying stage.

Metal degreasing specialists from the Centre Technique des Industries Mécaniques (CETIM), an independent French technical organisation specialising in the mechanical industries critically reviewed the LCA. The CETIM review confirmed solvent cleaning as the right technique to be used when metallic parts needed to be dry for subsequent processing.

BAE Systems' votes for trichloroethylene

Cleaning in the aerospace industry is still often solvent-based, trichloroethylene, and it can prove a tough act to follow, as BAE Systems, Samlesbury had found. In order to improve quality, sustainability, and safety of the cleaning process, the company looked for an alternative cleaning agent. Over a period of four years, the company investigated pretty well all options, including water-based cleaning agents and other solvents such as hydrocarbons and n-Propyl Bromide (nPB), but none could match up to Neu-Tri E trichloroethylene offered by Safechem Europe, says the solvent supplier.

Only Neu-Tri E was capable of reliably removing all the contaminations that occur through the use of up to 16 different oils and greases during the manufacturing process, and this resulted in an approval for NEU-TRI E trichloroethylene by BAE Systems and massive reduction in solvent consumption.

The chlorinated solvent is used in a new, closed cleaning facility which operates under vacuum. It is designed to clean 12 aluminium sheets of 2,000 by 2,600 mm or a mass of 700 kg in one cycle. With this capacity, the new degreaser is the largest machine of its kind in Europe, and, potentially, the world.

The cleaning process is carried out fully automatically and includes high pressure spray washing, vapour degreasing, and vacuum drying. At the end of the 30 to 40 minute cleaning cycle, the trichloroethylene is collected, distilled, condensed and absorbed into a carbon bed within the facility, so no solvent fumes occur when the door opens.

The chemical is supplied using Safechem's Safe-Tainer closed-loop transfer system, a state-of-the-art delivery and handling system for solvents that consists of two separate, specially designed containers, one for fresh and one for used solvent. Each container is delivered with a standard drum inside, with the steel container protecting the drum, preventing damage or spills. The containers are easy to handle and to store, and allow the safe management of chlorinated solvents on site.

During solvent transfer to the cleaning machine, a leak-free, dry-break coupling prevents spills and vapour emissions. When transferring used solvent from the cleaning machine to the Safe-Tainer container, a dry-break coupling adapter and a vapour return connection prevent emissions. This safeguards the operator and environment from potential contact with the solvent.

This, in combination with a new state-of-the-art degreaser, has seen the consumption of solvent dramatically reduced - 5 tons a year to less than half a ton, while the system meets all specifications of the Solvent Emissions Directive (SED).

Safechem also offers a simple and efficient solutions to monitor and maintain the quality of Neu-Tri E trichloroethylene. Due to the rising concentration of oils and greases and their decomposition products that are removed from the aluminium surfaces in the cleaning process, the chlorinated solvent slowly degrades. Safechem's Maxicheck test kit and business logbook allow operators to check the alkalinity level and the acid acceptance of the solvent regularly in an easy and quick manner and plot the results. If necessary, Maxistab stabiliser can be added to keep stabiliser concentration at the optimum level. This not only supports maximum cleaning quality, it also helps BAE Systems protect its cleaning facility against acidification and corrosion, and minimise solvent usage via an extended life-span.

First published in Machinery, May 2012

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents

Source: Safechem Europe

Environmentally friendly degreasing with solvents