Specifically, Airbus and Boeing state that, between now and then, more than 30,000 civil aircraft holding at least 90 seats are needed (Airbus: 33,000 over 100 seats; Boeing: 37,240 over 90 seats), plus nearly 6,000 smaller craft (Bombardier: 5,700 60- to 100-seaters). Very roughly speaking, about two-thirds of demand is for new capacity, and the rest is for replacements.

Airbus and Boeing’s forecasts are based on a prediction of average annual global passenger demand growth: Airbus’s is 4.5% per annum; Boeing’s 4.8%.

There are huge regional divergences inside those averaged figures; both reports point out that the great market for all of these planes is Asia. In Boeing’s demand forecast to 2035, Asia takes only slightly less than the total combined number of aeroplanes delivered to North America and Europe (15,130 compared to 15,900, of which Europe’s share is 7,570).

Simply put, industrial development of countries with a combined population of 6 billion would be responsible for the growth. But Airbus points out that in markets like China and India, a more significant driver will become ‘private consumption’; development of the kind of middle-class wealth that makes a plane ticket affordable.

Urbanisation is another significant global trend, according to Airbus, whose report states that by 2035, 62% of the world’s population will live in cities. By that time, the number of large cities – it calls them ‘aviation mega-cities’ – will rise by 70% to 93. Those places alone will generate 35% of world GDP in 2035, it predicts and, more to the point, will generate 2.5 million long-haul passengers a day, more than double today’s figure.

The aerospace OEM adds that many of these aviation mega-cities have airports that are ‘schedule-limited’, a term that seems to mean that they cannot run as many planes as the market would support in an ideal world. It goes on to argue that this is why its future is good: “Larger aircraft like the A380, combined with higher load factors, make the most efficient use of limited airport slots”. The widebody aircraft sales it predicts – more than 9,500 planes, including the A380 – are worth 54% of the total value of the 33,000 to be delivered over the next 20 years.

Unsurprisingly, Boeing sees the market differently – it has no equivalent to the A380. Although it predicts sales of 9,100 wide-body aeroplanes to 2035, that would include a ‘large wave’ of replacement demand. It adds: “Boeing projects a continued shift from very large airplanes to small and medium widebodies, such as the 787, 777 and 777X.”

In contrast, its report emphasises the ‘especially strong’ single-aisle aircraft market in emerging markets and, driven by low-cost carriers, that has increased 5% for the company over the last year alone. It predicts it will sell 28,140 planes with 90-230 seats in that segment (Airbus: 23,500, of which 39% would go to Asia-Pacific). Bombardier is also keenly exploring the market of small (up to 160 seats) single-aisle aircraft, thanks to its two new CS100 and CS300 models of jet.

And demand is expected to continue despite “recent events that have impacted the financial markets”, said Randy Tinseth, vice president of marketing, Boeing Commercial Airplanes, in early July at the Farnborough International Airshow. He was probably referring to the Brexit vote only a fortnight before.

These forecasts make for pleasant reading in the UK, aerospace supplier to the world, where OEMs currently have 13,000 aircraft amounting to nine years’ work and worth nearly £200 billion, in hand, according to the Aerospace Growth Partnership’s Means of Ascent report published in August (these figures cover both civil and defence contracts).

In macro terms, UK aerospace industry sales grew by 6.5% last year, compared to 2014, to £31.1 billion. Exports, mostly to the USA and the Middle East, grew by £700 million in that period, to £27 billion (87% of the total).

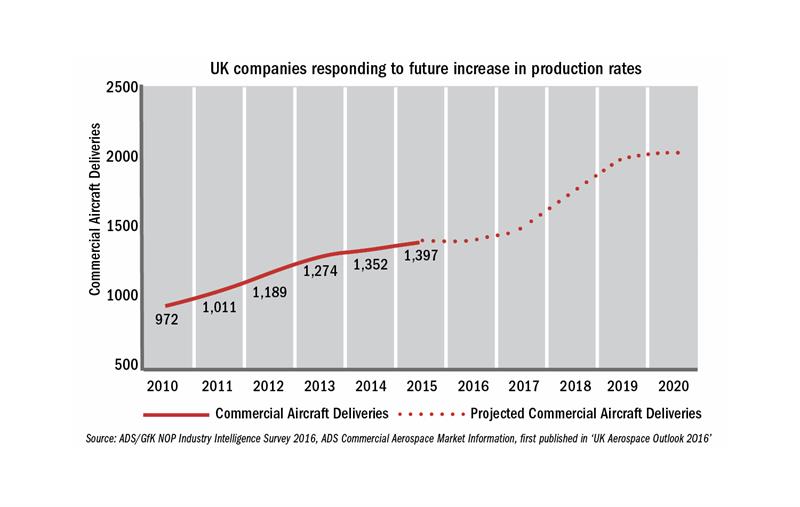

A survey conducted in February and March this year for industry body ADS (and published in its Aerospace Outlook report in June) offers a picture of how the supply chain of the UK aerospace industry, which employs 128,000 directly and 153,900 indirectly, is now developing.

First, it is confident. Almost half, 45%, predicted that their company would grow by up to 10% in the 12 months to next spring; 54% predicted even larger amounts of growth. Business is coming from growth of existing business (73% of respondents); new export business opportunities (63%); and UK opportunities (49%).

Second, it is investing. In the survey, 68% of respondents said they have plans to increase investment, as opposed to 7% decreasing investment, and 24% keeping it the same. Those companies that are increasing investment were asked where the money is going; the main areas are business development (49%); R&D (47%), way up compared to last year, when it ranked fifth; production and assembly (47%); design and engineering (45%); and apprentices and training (37%).

Now that the future looks bright, businesses are bringing in the next generation. The survey found that 60% of respondents now employ apprentices and trainees (they now number 4,100). That’s way up from the 19% recorded in the dark days of 2009. Also, more than a third of aerospace companies (39%) are investing in apprenticeships in production and assembly jobs, the most populous worker group in the aerospace industry, comprising 35% of all employees.

Third, the UK aerospace industry is looking ahead. The ADS reported that, although successful, 2015 was not an easy year: “There continue to be major challenges as pressure increases from international competitors and customers demanding continuous and sustained improvements.”

To keep up with the market, the government-industry development agency Aerospace Growth Partnership’s new initiative, the Supply Chain Charter, aims to encourage/force lower-tier suppliers into performance improvement projects, such as the existing SC21 initiative. Happily for machine vendors, one of its aims is promoting investment in production technology. Its signatories, as of October, are Airbus, Bombardier, Boeing, GE, GKN, Leonardo Helicopters, Rolls-Royce, Safran, Spirit Aerosystems, Thales and UTC Aerospace.